A Guest Blog Post by Brian Leggat from https://www.bushcraftsurvivalacademy.com/

A Nessmuk-style bushcraft knife with a scandi grind–why? (Photo Credit Author)

As a Bushcraft and Survival skills instructor, students often ask me which knife grind gives the best bushcraft knife? The modern-day bushcraft community seems to be settling on the Scandi grind as the ‘go to’ knife grind for bushcraft use. I am not sure that I agree.

I will let you into a little secret, personally I am not that keen on the modern Scandi grind on a general-purpose bushcraft knife. Whilst it excels for wood carving tasks, I find it cumbersome to use around the camp kitchen and for other general activities.

Many years ago, I attended my first bushcraft taster course where the instructor loaned me the use of his Woodlore style knife to process pine needles to make pine needle tea. I found my pocketknife, all I had on me at the time, to be far more effective in this slicing task. This experience kindled my love/hate relationship with the Scandi grind.

I now own many Scandi grind knives. Indeed, one of my favorite Sloyd style carving knives is a Scandi grind. In this specific role, it is exceptionally good. In the broad spectrum of bushcraft uses that a general-purpose knife needs to be proficient at, I have often found the modern bushcraft knives with a modern Scandi grind are deficient in at least some of these tasks especially ones requiring slicing, like food preparation tasks. Outside of basic wood carving activities, the main thing we use our knives for is processing and preparing food.

Early in 2020, when a well-known and popular leader in the bushcraft community released a skinning knife in the Nessmuk style with a Scandi grind, I had to ask myself why? The original purpose of this design of knife, primarily to skin and butcher larger game, is better served by a completely different edge profile.

So why has the Scandi grind become the default grind for a bushcraft knife, almost to the exclusion of anything else? Why is it appearing on specialized knife designs that would perform their function far better with a different grind? Does the Scandi grind make the best bushcraft knife?

I have my theories, some of which I’ll explore in this blog post.

The Scandi Grind, What is it?

Scandi grind, short for Scandinavian grind, is also sometimes known as a zero grind. Typically, the blade remains rectangular until the grind line. An equal amount of material is ground off each side of the blade at the grind angle, meeting in the middle to form the edge. This angle tends to be around 30 degrees inclusive on a modern bushcraft knife.

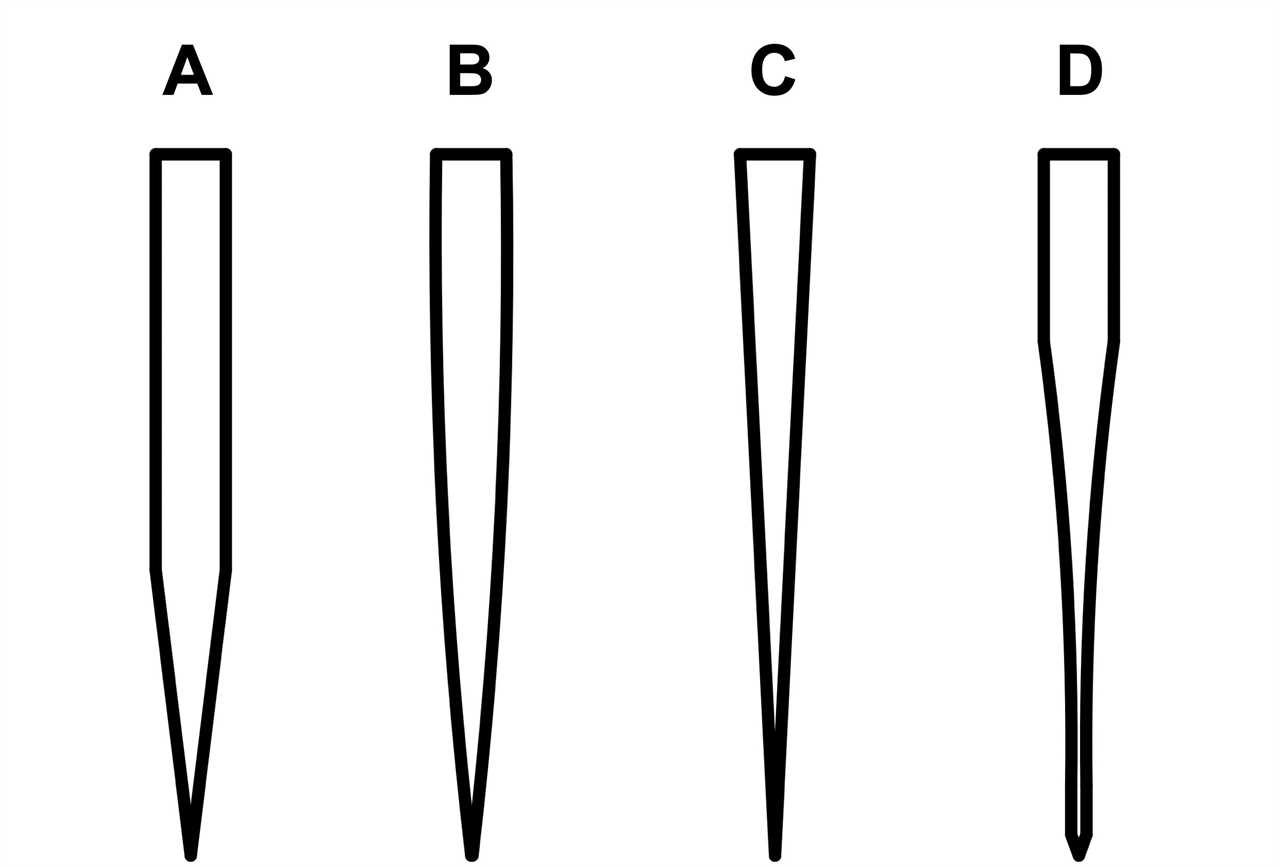

The image below shows and compares four popular knife grinds.

Four of the most popular knife grinds in use on general purpose bushcraft knives. (Photo Credit: Author)

A – Scandi – this grind has become the most popular and common place grind on bushcraft knifes of the modern era and is described in more detail above.

B – Convex – in cross section, the convex grind looks a little like a pointed ‘Spitzer’ style rifle bullet, a curve continuously falling away from the spine until it meets and forms the edge. This grind is very robust and for this reason, is commonly found on axes. The increasing curve helps protect the edge after the initial cut is made forcing the material apart with a wedging action. If incorrectly sharpened, a convex edge can quickly become too thick and wedge like – this is often the reason the convex edge gets a bad name.

C – Full Flat – the full flat grind tapers evenly on both sides of the knife from the spine to the edge. On small carving style bushcraft knives, the full flat may also form the cutting edge, whereas larger bushcraft knives often utilize a secondary bevel or micro bevel to form the cutting edge.

D – Hollow – the hollow grind allows a fine cutting edge to be established and was commonly used on cutthroat razors. These days you are most likely to find a hollow ground blade on a bushcraft knife that has been designed for skinning. The downside of this type of grind is that the hollow grind leaves little material supporting the edge meaning it can be relatively weak and easy to damage.

Best Bushcraft Knife: The Scandinavian Tradition

The Scandi grind traces its origins all the way back to the Viking era Seax knife. Each Scandinavian region has its variant of a general-purpose knife such as the Finnish Puukko or the larger Leuku of the Sami peoples.

The Puukko is a relatively small knife with a blade only the width of the palm of the hand. Its uses are innumerable including detail carving, cleaning fish and game, general chores and even self defence to name but a few.

The larger Leuku has a longer and stronger blade suited for light chopping tasks such as gathering shelter poles and de-limbing trees, clearing brush from camping sites and butchering larger joints of meat. In many ways, the Leuku is a substitute axe especially when used for chopping and splitting kindling for fires.

The Puukko and Leuko are often paired to make a set of knives with a high degree of practical utility.

The design of the Puukko has remained virtually unchanged for 2000 years, with 1000-year-old specimens in museums and private collections that are easily recognizable as examples of the form.

Viking era knife approximately 1200 years old found in the Belgjinose region of the South Jotunheim Mountains. (Photo Credit: Vegard Vike, Secrets of the ice project, University of Oslo)

Traditional Puukkos have a Scandi grind between 17- and 22-degrees inclusive angle making them good at detailed carving in the relatively soft birch, spruce and pine of the boreal region, as well as slicing and other general food preparation tasks.

The modern trend has been to change the angle of the Scandi grind closer to 30 degrees. More in line with the cutting edge of European wood working tools, like chisels and plane irons. My theory for this is that it more readily accommodates working the European hardwoods like ash, cherry, beech, and oak.

Whilst changing the angle of the grind adds significant strength to the blade immediately behind the edge, preventing edge rolls or chips on these harder woods, it significantly decreases the utility of the blade, for example, making it quite cumbersome on basic slicing tasks like food preparation.

Pros of a Scandi Grind

The Scandi grind has a lot of positive traits:

- It’s easy to sharpen, especially by beginners and requires less skill in the field to keep it sharp.

- It’s set up for wood carving tasks, especially for making relatively shallow cuts comparable to a chisel.

- It can have a thin edge but retains blade weight/stiffness

- The wedge transition helps break up the chip from deep cuts

- It has relatively fine handling characteristics which makes it useful for detail carving

- It’s relatively cheap to make

- It’s relatively easy to make with lonely a few power tools or only hand tools

Cons of a Scandi grind

But it also has a few negative traits, especially in its modern incarnation:

- It’s not ideal for meat and food prep especially slicing things like root vegetables, boning a joint of meat or slicing a tomato

- Lots of material has to be removed from each bevel to sharpen it correctly

- Removal of edge damage takes a long time (and removes lots of material)

- It can have a relatively delicate unsupported edge that has the potential to be easily damaged.

At first glance, the Scandi grind appears to have far more positive traits that negative ones. However, when we look at these closely, most of the positive traits relate to its excellent wood carving abilities. If we are honest how many of us are using our knives for predominately wood carving activities? I suggest most of us use our knives in a more general-purpose way and in these roles the negatives of the Scandi grind come to the fore.

Did Our Forefathers Use a Scandi Grind Knife?

Looking back at the golden age of Camping and Woodcraft, in the late 19th and early 20th entry, the influential individuals of that era lived outdoors in ways that most of us can only aspire to these days.

Did the bushcraft legends of the day like Nessmuk, Kephart, Jaeger and Whelen, consider the Scandi grind to make their best bushcraft knife?

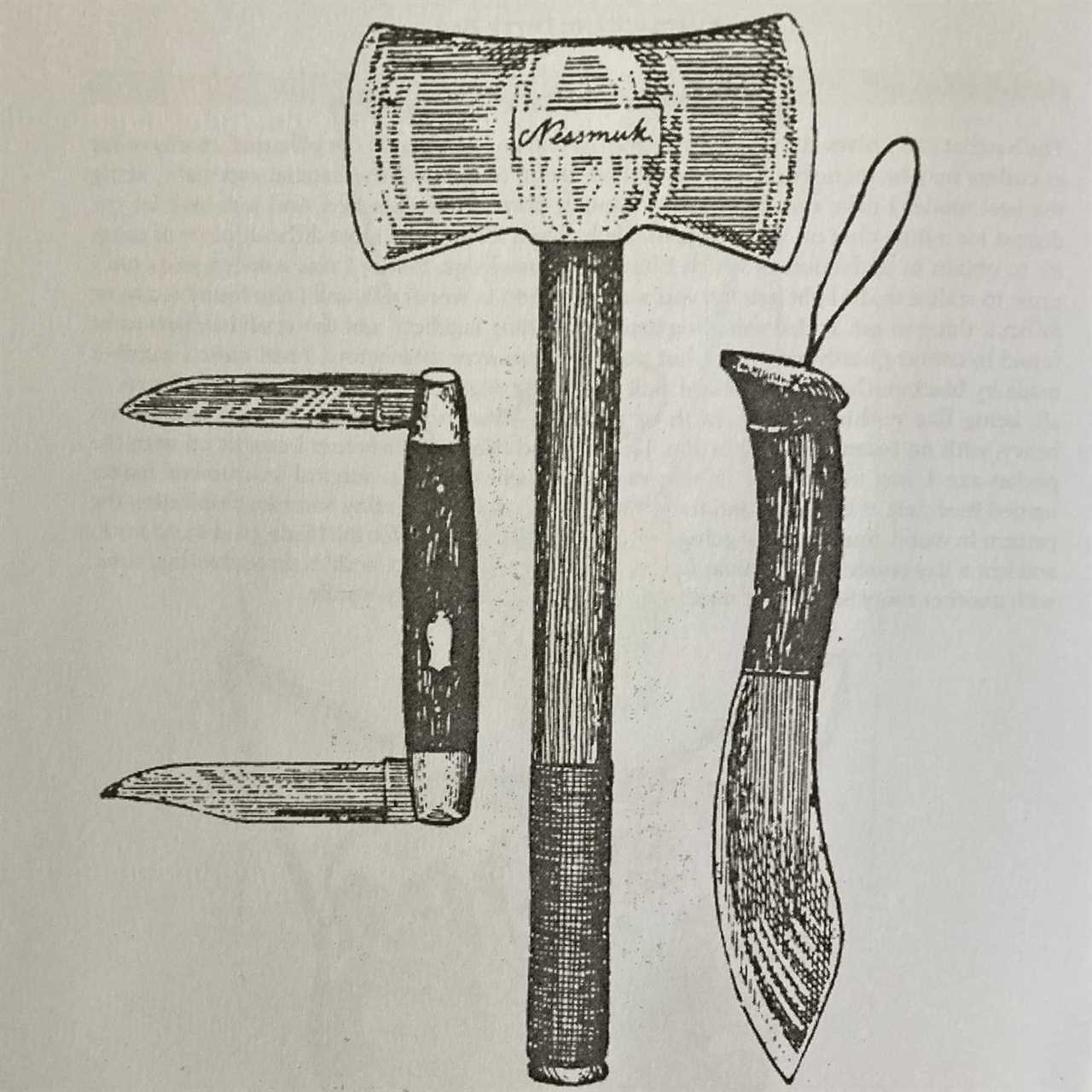

From Woodcraft and Camping by George Washington Sears, published 1884.

Taking the Nessmuk knife as an example, here is what the man himself had to say:

“A word as to knife or knives. These are of prime necessity, and should be of the best both as to shape and temper.

The one shown in the cut is thin in the blade, and handy for skinning, cutting meat, or eating with. The strong double-bladed pocket knife is the best model I have yet found, and, in connection with the sheath knife, is all sufficient for camp use.”

Kephart, Jaeger, and Whelen expressed similar views.

The emphasis on the use of these knives, at this time, tended towards the processing of game animals and kitchen tasks, rather than the woodcraft tasks associated with modern bushcraft practices. Not one of these knives recommended and in use in this era had the now common ‘Scandi’ grind, despite an estimated 2.1 million Scandinavian migrating to the US between 1820 and 1920 – more than enough to influence the views of the writers of the time.

The knife Nessmuk described almost certainly had a full flat grind with a secondary bevel. He considered this knife his best bushcraft knife to meet his specific needs. I think Nessmuk would have been disappointed to see his lightweight skinning knife reimagined with a thick heavy blade, sporting a modern style Scandi grind.

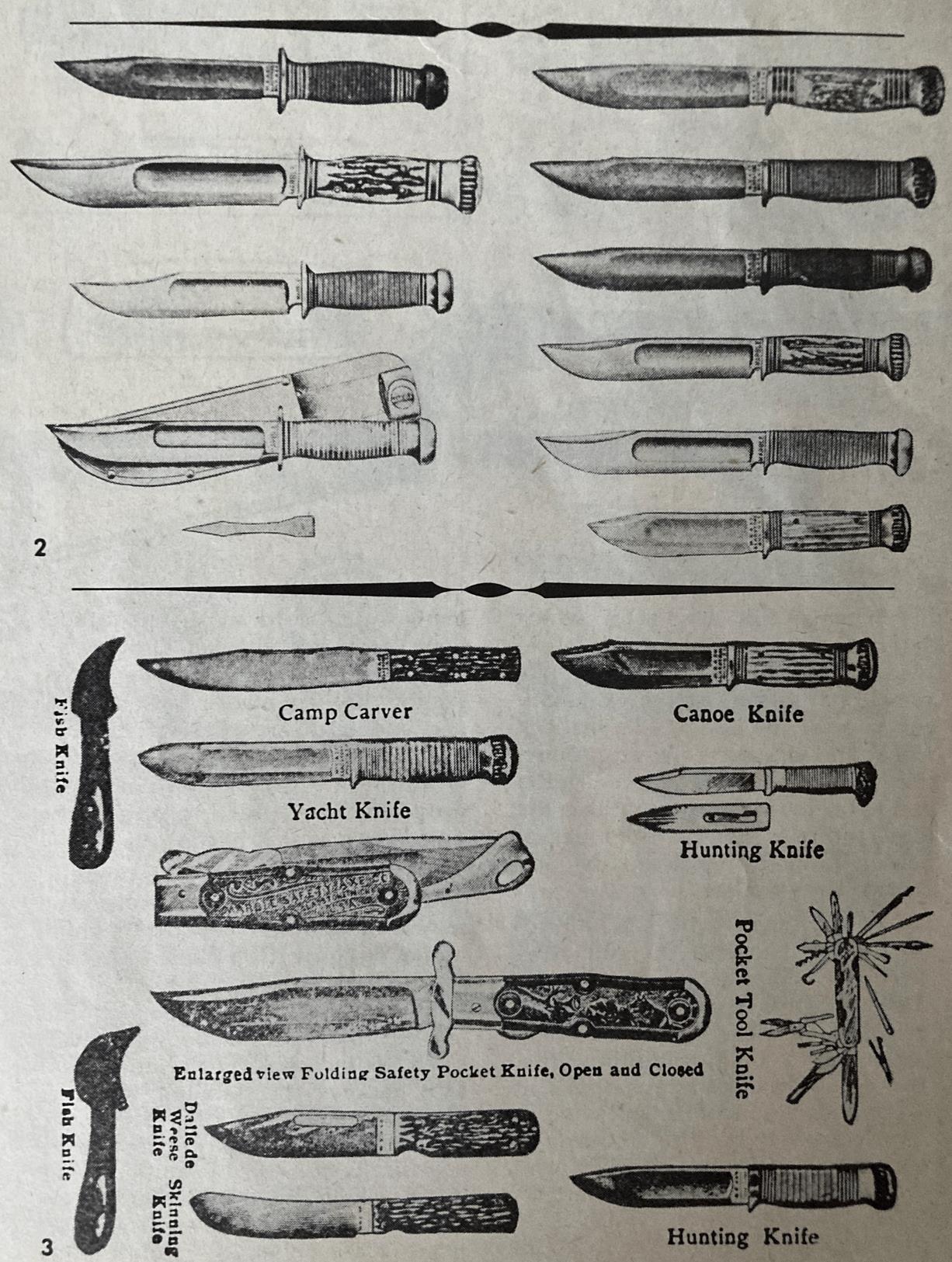

Popular camping and hunting knives from the Marbles company early to mid 1900s. (Source: Guns and Ammo guidebook to knives and edged weapons 1974, pg 181)

The popular knife maker Marbles from this period offered a wide range of knives suitable for every task, practically inventing the hunting knife genre. This started in 1899 with the Ideal model, followed by the Expert in 1906, and then in around 1915, the Woodcrafter. These knives set the standard for an outdoorsman knife until the 1960s with almost every major cutlery company offering versions of Marbles most popular knives. None of these knives had a Scandi grind; all were a version of a flat grind with a secondary bevel forming the cutting edged formed the best bushcraft knife of the period.

Coming forward to the 1970s and 1980s, to a time before the name ‘Bushcraft’ had been coined and come into popular use, did the popular hunting, camping and survival knives of the time utilise a Scandi grind?

Short answer, no.

Before the 1990s, most people’s vision of what now broadly termed ‘bushcraft’ is fell under the title of hunting or ‘survival’. At the time, the knife industry had been heavily influenced by the Rambo movies and most knives being sold suitable for ‘wild camping’ had moved away from the earlier woodcraft and camping era hunting style knives to a more militaristic style, usually with a saw back edge and a built-in survival kit.

The first image, taken from a 1970s article in the Guns and Ammo guide to knives (1974, page 119) shows a typical range of survival knives of the period. Not a Scandi ground blade to be seen.

Popular survival knives of the 1970s. (Source: Guns and Ammo guide to knives 1974, page 119)

The second image, the lead image from an article on survival knives taken from the ‘Survival Weaponry and Techniques Manual 1989’ (a U.K. survival publication) shows a wide selection of knives of the era (page 193) only one of which has a Scandi style blade grind.

A selection of popular survival knives of the 1980s. (Source: Survival Weaponry and Techniques Manual 1989, page 193)

A slight aside, but I found it interesting that in this historic article, very little page space was given to the discussion of knife grinds (about one paragraph) versus the discussion on the pros and cons of different tang types which took up nearly a whole page! How times have changed.

An advert in the same publication, from a leading UK retailer of knives at the time, shows a wide range of popular knives that could be considered the best bushcraft knives of the day. Nearly all of which are in a survival style without Scandi grinds.

Popular knife sales of the late 1980’s. Scandi grind knives were not popular. (Source: Survival Weaponry and Techniques Manual 1989 page 38)

From these examples, we can draw the the conclusion that up until the early 1990s the Scandi grind blade was not in popular use and was relatively limited to specialist tools and particular ethnic regions.

Best Bushcraft Knife: Why is the Scandi Grind so Popular?

A bushcraft knife in the Woodlore style. (Credit: Author)

Well, my money is on the influence of the well-known and popular bushcraft expert and TV presenter Ray Mears from the UK.

In the late 1980’s, Ray developed the design for his Woodlore style knife, which by now must be one of the most recognizable and cloned knives within the bushcraft community and is widely considered the best bushcraft knife.

Ray worked with prominent UK knife maker Alan Woods to bring his design to reality. In Alan’s own words:

“He wanted a smallish knife, handmade and as British as possible that was to become the Woodlore Neck Knife due to the sheath concept that allowed carry with a cord around the neck or slung under the arm for discrete carry or Arctic use. He wanted carbon steel as he felt stainless had no “soul”, a full, non-tapered tang and the short Nordic grind, a wood handle from native trees and a design that was devoid of frippery.”

“Most people who attended his courses weren’t necessarily “knife people” and that it would be easier for them to sharpen if they could lay the whole bevel on the hone. Also, he needed the wedge-like edge that it produced for specific bushcraft tasks and controlled woodworking cuts.”

http://www.alanwoodknives.com/the-woodlore-knife-story.html

There is no doubt in my mind that Ray’s strong links with the Sami peoples of the Scandinavian boreal forest regions introduced him to knives of the Puukko tradition with its Scandi grind and its inherent benefits to wood carving and novices learning to sharpen. Equally, I believe Ray is the one who initiated the trend for the angle of the Scandi grind to be around 30 degrees, mimicking common wood working tools.

I also have no doubt that the popularity of Ray Mears as a champion of bushcraft in the 1990s influenced a generation of outdoors practitioners – the Woodlore knife became the must-have knife for practicing bushcraft and to a degree today still is. In effect it became fashionable with the best dressed of the new breed of ‘bushcrafters’, sporting a Woodlore style knife as the best bushcraft knife.

This fashion has been further re-enforced by the promotion and popularity of the Mora companion style knives, given away to attendees of Ray’s courses. These relatively cheap but robust knives have become the staple of bushcraft instructors as a course knife for students to use.

The Scandi grind trend has morphed with time into the Scandi grind being the ‘only’ grind suitable for the practice of bushcraft, to the point where almost every ‘bushcraft knife’ now has this grind irrespective of the original design intent for the knife or whether the Scandi grind is entirely suitable for the purpose – the modern Nessmuk knife being a prime example.

Best Bushcraft Knife: Summing it Up

Does the Scandi grind make the best bushcraft knife? Well, in my view it doesn’t. Like everything in life, the Scandi grind is a compromise. It excels at some things and is poor at others. Only you can decide if a Scandi grind on a knife suits your intended purpose.

If that’s true, why is the Scandi grind so popular and so prevalent on the ‘best’ bushcraft knives? Put simply, it’s fashionable. The current leaders and influencers in the bushcraft community have promoted the use of Scandi ground blades, partially to ride the wave of popularity of the Woodlore knives and partially by being in a feedback loop, all being influenced by each other’s best practice.

If we look back to the late 1800s and earlier, there wasn’t a standardized knife to do what we now call bushcraft, most people had a ‘make do’ attitude using what they had to hand, often repurposed kitchen or butchers knives. Custom knives, where they existed, were as individual as the blacksmith who made them.

Moving into the early 1900s, companies like Marbles promoted their own products as the best bushcraft knives around at the time. With innovations in marketing and advertising ensuring sales, other companies jumped on the band wagon so as not to get left behind and miss out on their share of the market. This ensured that the hunting style knife became the ‘best’ type of knife up until the 1970s.

A new generation of knife makers came on the scene in the 1970s offering custom options and something a little different. Makers like Jimmy Lile and Jack Crain produced militaristic style knives that were picked up by Hollywood in films like Rambo and Commando. Thus started the popularity of survival style knives that lasted well into the 1990s.

The influence of Ray Mears and his Woodlore style knife, designed for a specific but relatively limited purpose brings us up to the present day, where it seems the best bushcraft knife is any knife whatever the shape, as long as it has a Scandi grind.

Recognizing that any knife grind is a compromise and better suited to some tasks over others, the primary purpose you intend to use your knife for should be the driving factor in your choice of both knife style and grind. If you want a knife primarily for woodworking tasks that requires limited skill to keep sharp, then a Scandi grind knife may make the best bushcraft knife for you.

My advice is to choose the edge that is best suited for your needs, the tasks you are doing and the environments you are using your knife in, over following fashion.

What’s my preference? Well, for personal use I prefer a high sabre or flat grind with a convex secondary edge or a full convex grind. I find these knife grinds to be very versatile especially at the tasks where a scandi grind struggles.

However, I often use a Scandi ground knife when instructing because of the benefits to beginners and well to be truthful, because it’s expected.

Brian is the founder of https://www.bushcraftsurvivalacademy.com/

Brian also has an article on his blog about the best bushcraft knife for chopping and batoning.

The post Best Bushcraft Knife: The Great Scandi Grind Controversy appeared first on WillowHavenOutdoor Survival Skills.

By: Creek

Title: Best Bushcraft Knife: The Great Scandi Grind Controversy

Sourced From: willowhavenoutdoor.com/best-bushcraft-knife-the-great-scandi-grind-controversy/

Published Date: Wed, 17 Mar 2021 22:21:05 +0000

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

CampingSurvivalistHuntingFishingExploringHikingPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

CampingSurvivalistHuntingFishingExploringHikingPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions