An easy-going day hike with a bit of off trail navigation leading to the wreckage of a US Air Force C-45 that crashed into Middle Mountain in West Virginia's Laurel Fork South Wilderness.

Trailhead elevation 3,110'

Water throughout, along the Laurel Fork River

Don't miss camping at the Laurel Fork Campground

Hike to the Laurel Fork Wilderness USAF C-45 Plane Crash Site

There are multiple routes to access the crash site, but the most straightforward path begins at the Laurel Fork Trail/TR 306, located near the southwest edge of the Laurel Fork Campground. The trailhead parking can accommodate three to four vehicles, with additional secondary parking available nearby in the rare event that the main lot is full.

Starting from the clearly marked trailhead, hikers follow an unmarked path initially running parallel to the Laurel Fork River along an abandoned forest road for just under 0.6 miles. After crossing a small stream at the 0.6-mile mark, the trail winds through a mix of hardwoods and new growth pines.

Although the trail remains relatively easy to follow for the next quarter mile, it eventually fades away. When this occurs, hikers should continue following the dry creek bed until the trail becomes visible again a short distance ahead.

At the 1.5-mile mark, the trail intersects with the Beulah Trail/TR 310.

From the intersection with the Beulah Trail, hikers should proceed straight along the Laurel Fork Trail for another quarter mile. Around the 1.75-mile mark, hikers should find a small rock cairn along the trail, immediately followed by a stream flowing through a ravine on the right.

Here, hikers should veer right and follow the stream uphill for a few hundred yards until reaching the wreckage of the crash. The tragic tale of the doomed flight unfolds as such:

In the afternoon of March 22, 1960, four people, including current and former USAF personnel, boarded a twin-engine USAF C-45 in Richmond, Virginia, en route to Ohio's Lockbourne Air Force Base - tragically, they were never seen alive again. The details surrounding the flight are anything but clear, but it appears that aircraft encountered a loss of lift, presumably due to the formation of ice on its wings, somewhere in the Mountain Lakes region of West Virginia. At approximately 5:20 PM, after covering a distance of roughly 200 miles, the pilot of the C-45 communicated with the Elkins Airport via radio shortly before vanishing from radar.

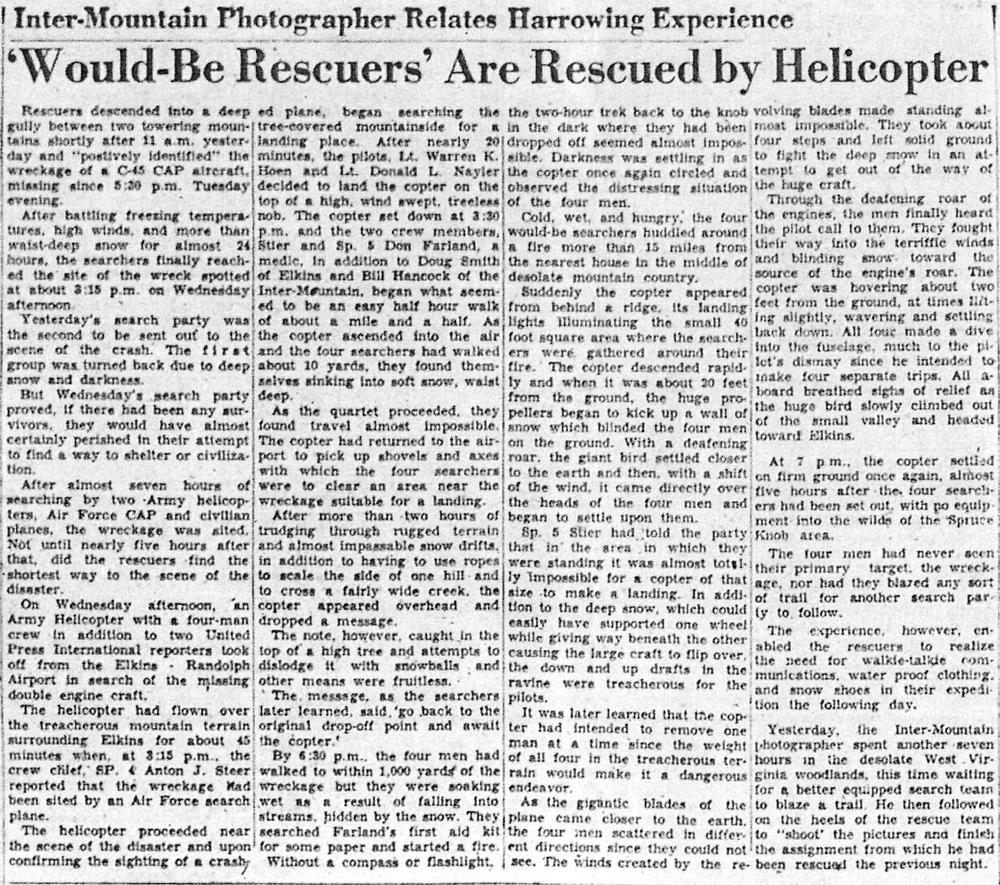

After Elkins Airport failed to re-establish radio communication with the C-45, search and rescue teams were dispatched. An initial 65 person search party, including 15 USAF officers, 40 senior members of the Civil Air Patrol, and 10 cadets, was dispatched to search the Spruce Mountain, Harman, Rich Mountain, and Beverly areas where residents had reported a low-flying plane the previous evening. In addition to the crew searching on foot, two USAF C-47s, one C-45, one Aero Commander, and two helicopters were deployed to assist the search. Despite their efforts that evening, they were not able to locate the crashed C-45.

The next morning, search and rescue teams were sent out again. Despite facing blizzard-like conditions, one of the helicopters managed to locate the crash site at 11:38 AM. Later that day, after the site was confirmed, teams forged a path through thick forest and battled through snow drifts ranging from four to six feet deep. When the snow became too difficult to navigate, around twelve men abandoned their vehicles and trekked a mile and a half wearing snowshoes. However, with a fresh layer of 10 inches of snowfall and snow drifts reaching up to 12 feet, their efforts were no match for mother nature, leading to the suspension of the search until the next day once again.

The next morning, an Army helicopter carrying a crew of four and two United Press International reporters departed from the Elkins-Randolph Airport. After navigating through 45 minutes of perilous mountain terrain, another aircraft in the area spotted the crash site. The helicopter then approached the area of disaster, scanning the tree-covered mountainside for a suitable landing spot. Eventually, it settled atop a high, wind-swept knob devoid of trees, and a four man team (two crew and two reporters) disembarked to begin their search.

Their progress was immediately hindered as they found themselves sinking waist-deep into the snow after just 10 yards. As they pressed forward, traversing the mountainside proved exceedingly difficult. In addition to deep snow, the men faced ferocious wind and bone-chilling temperatures. Meanwhile, the helicopter that had dropped them off returned to the Elkins-Randolph Airport to retrieve shovels and ice axes, tools that were intended to help the four men clear an area adjacent to the crash site and facilitate a safe landing spot for the helicopter.

After more than two hours of navigating rugged terrain and nearly impassable snow drifts, including using ropes to ascend one hillside and crossing a wide creek, the helicopter returned overhead and dropped a message. Unfortunately, the note got snagged in the top of a tree, and efforts to dislodge it with snowballs proved futile. The message, which they later discovered, instructed them to "return to the original drop-off point and await the helicopter."

Unable to retrieve the note, the men pressed on. After seven hours, they had advanced to within 1000 yards of the wreckage, but they were soaked from falling into snow-covered streams. Around this time, they rummaged through their first aid kit, found some paper, and lit a fire.

As darkness descended rapidly and with no compass or flashlight at hand, the group decided that their best course of action for survival that evening was to stay put around a fire. Considering the dreadful conditions, the idea of a two-hour journey back to the original drop-off point seemed utterly impossible.

Cold, wet, and hungry, the crew huddled around their fire when suddenly the helicopter emerged from behind a ridge and hovered directly above them. As it descended upon them, its blades stirred up a flurry of snow, obscuring the men's vision. They scattered in different directions, unconvinced it could land safely. Eventually, with the helicopter hovering a mere two feet above ground, the men leaped aboard and were flown to safety.

The next morning, after two failed attempts, search teams finally reached the crash site on foot. It was there that they found the four passengers aboard the crashed C-45, tragically charred to their seats. Cupp Funeral Home later facilitated their transport off the mountain, reuniting them with their grieving families.

The C-45 was the WWII iteration of the popular Beechcraft Model 18 commercial light transport. Beechcraft produced a total of 4,526 of these planes for the Army Air Forces between 1939 and 1945, spanning four different versions: the AT-7 Navigator navigation trainer, the AT-11 Kansan bombing-gunnery trainer, the C-45 Expeditor utility transport, and the F-2 for aerial photography and mapping.

In the 1950s, Beechcraft underwent a comprehensive reconstruction of 900 C-45s for the Air Force. These overhauled planes were assigned new serial numbers and designated as C-45Gs and C-45Hs, remaining in active service until 1963, primarily fulfilling administrative and light cargo duties. There is reason to believe that the C-45 that crashed in Laurel Fork South Wilderness was among the refurbished aircraft.

Those who perished were: pilot, Captain William Gray Barbour (Florence, SC), Civil Air Patrol Lt. Col. and teacher Elizabeth Bryant Tucker (Richmond, VA), Sgt. Monroe L Hatch (Sumter, SC), and North Carolina Civil Air Patrol Education Director and former Sgt. of the Technical Trailing Squad 3750 Clarence Bailey Bomar, Jr. (Raleigh, NC). All four of their death certificates indicate extensive third degree burns caused by the crash.

If you intend to hike out to the site, kindly pay respect to those who tragically lost their lives that day by leaving all remaining crash debris undisturbed at the site. There is no cell service within 30 minutes of the trailhead, so hikers should consider downloading the area to offline maps prior to venturing out. For those interested in camping for the night, the Laurel Fork Campground is an excellent, seldom used campground with picnic tables, fire rings, pit toilets, and easy access to the Laurel Fork River.

https://www.greatamericanhikes.com/post/hike-to-the-usaf-c-45-plane-crash-site-in-laurel-fork-wilderness

CampingSurvivalistHuntingFishingExploringHikingPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

CampingSurvivalistHuntingFishingExploringHikingPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions