Sponsored by Garmin

After all the time, effort, and research that goes into a successful day on the water, the last thing any angler wants is to have it wasted by clunky wading, loud talking, or heavy boat traffic spooking fish and blowing spots.

However, just as often as we have watched fish spook beneath our feet, we have also seen the guy blasting music and stomping beer cans put on a fishing clinic for all the quiet anglers around him.

After seeing countless noisy and careless anglers have seemingly no impact on fish, we were curious to see what the science had to say about the sounds we make and how fish respond to them and, once and for all, get to get to the bottom of the age-old question: Should you be Quiet While Fishing?

Can Fish Hear?

The first question to ask when considering whether you should be quiet while fishing is whether the fish can hear you at all. The answer may be obvious, but the way in which they hear may surprise you.

How Fish Hear: The Inner Ear System

The inner ear system of a fish

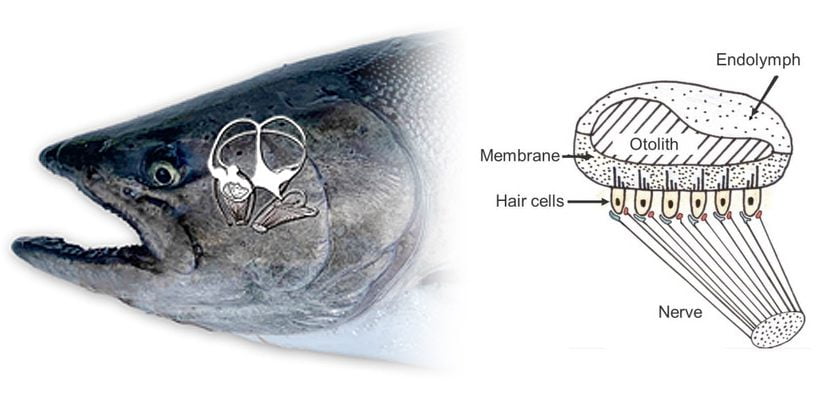

Fish, evidently do not have ears, but they do have an inner ear system. Since fish are roughly the same density as the water that surrounds them, sounds should theoretically pass undetected through their bodies. This is combated, however, by a group of small organs known as Otoliths.

Otoliths are located in the inner ear of the fish and are some of the few organs in the fish’s body that are denser than water.

When sound passes through the fish’s body, this difference in density makes the Otoliths move differently than the rest of the body’s tissues, sending signals through small hair cells to the fish’s brain that register as sound. Since each Otolith in the fish’s ear has a different orientation, these signals also allow the fish to determine what direction the sound is coming from and respond to the sound accordingly.

In short, this is the fish’s long-range source of hearing and is what picks up the majority of sounds that pass through the water.

Fun Fact: Otoliths are also the primary indicator used to determine a fish’s age and the ones found in Sheepshead (Freshwater Drum) are considered lucky and can even be turned into jewelry.

Katie O’Reilly via Twitter

The “lucky” Otoliths from a Sheepshead (Freshwater Drum)

How Fish Hear: The Lateral Line

Lateral line on a Bull Trout

For short-range sounds, fish rely on a complex network of cells known as neuromasts. The combination of these cells is what is known as the lateral line, running from head to tail in a visible line along the fish’s side.

Similar to the inner ear system, these cells also rely on vibrations in the water to transmit a signal. The vibrations picked up by this system often have to be as close as roughly two body lengths (more info here) and allow the fish to detect vibrations and movements in the water; some of which are caused by sounds.

This system is what allows fish to locate nearby bait, evade approaching predators, and swim alongside each other in schools.

Essentially, fish do not so much hear sounds, as they do feel them.

Does Sound Translate Underwater?

The sense of hearing that fish are able to gain from these systems is much more acute than you may think, with many fish having the ability to distinguish distinct sounds over long distances through the sensing of vibrations in the water.

This was demonstrated most notably by a Harvard study conducted by researcher Ava Chase. This study used a feeding system to reward Koi with food when they responded to a designated style of music. While the fish simply being able to perform the task was astounding in and of itself, the fish also showed the ability to distinguish very similar songs from each other, such as the recordings from two different blues musicians and even a classical song played in two different keys.

Koi Fish: music connaisseur

Although this study is very interesting, very few of us are heading out targeting Koi, and even fewer are targeting the blues-loving variety mentioned in this study. It does, however, demonstrate just how acute these fishes’ sense of hearing is when it comes to picking up man-made sounds in the water.

Thankfully for those more talkative anglers, sound has difficulty travelling from air to water. This means that noises above the water, such as loud talking, will have very little impact on the fish below, explaining why the rowdy cottagers in the pontoon boat are still able to pull up fish despite the noise.

Sounds that we make below the water, however, such as dropping pliers in an aluminum boat or clumsily wading down a riverbank can be heard by fish over great distances and can significantly impact fish behaviour.

What Sounds Do Fish Fear Most?

The fish’s association with the sounds that you make are not always negative. After all, we have all experienced a fish biting right after a fresh hole has been drilled in the ice or a fish coming to check out a big intrusive lure that has just hit the water. The behaviour of the fish in these situations is related to the associated outcome of the sound.

For example, nothing good has ever happened to a Brown Trout after something clumsily slides down a riverbank, just as nothing good has ever happened to a Bass when a kid stomps on the dock it is living under. On the other hand, sounds such as splashes in the water and cracks in the ice are often associated with food, drawing the fish’s curiosity and allowing you to get away with some of these noises when out on the water.

Angelo putting on a topwater Northern Pike clinic in the shallows of Kaby Lake.

So if natural sounds are capable of impacting fish behaviour, what does this mean for our big motors and electronics that running constantly as we approach our fishing holes? Cecilia Krahforst of East Carolina University addresses this question by first pointing out that modern outboard motors have a sound output of around 1,000-5,000 hertz. While this large number may sound significant, the auditory system of fish typically focuses on low-frequency sounds below 1,000 hertz, meaning that this sound is potentially much less disruptive than it would seem.

Another factor that goes into the disruptiveness of boats and motors is the level of background noise. In order for a noise to be disruptive for a fish, it has to be distinguishable from the background noise that already exists in the lake or river, including both natural and man-made noises. This means that fish in areas with high current or lots of boat traffic will be much less wary of the noise you make and will spook much less easily.

Anecdotally, this is something I have experienced firsthand with electric trolling motors.

When out Bass fishing, constantly starting and stopping a trolling motor in shallow or quiet areas often results in fish darting away from the boat and becoming virtually lock jawed. When approaching similar areas with the motor at a constant level, however, you are often able to sight fish for Bass that would have never let you get that close otherwise. While this is not scientific by any means, it does show how beneficial consistency and blending into the background can be when fishing with seemingly intrusive technology.

Sneaking into shallow water with a Garmin Force Trolling motor

Sneaking into shallow water with a Garmin Force Trolling motor

The Verdict

In summary, although fish are likely to hear the noises you make while out on the water, the intrusiveness of the sounds you make are largely going to contribute to how the fish react to your presence. This makes blending in with your surroundings much more important than simply being quiet and makes pressured bodies of water much more forgiving to loud anglers and big boats.

https://fishncanada.com/should-you-be-quiet-while-fishing-2/

CampingSurvivalistHuntingFishingExploringHikingPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

CampingSurvivalistHuntingFishingExploringHikingPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions